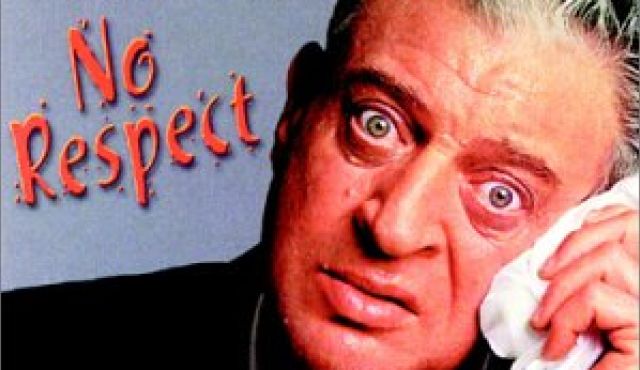

No Respect! Are Humanities the Rodney Dangerfield of Academia?

June, 2010 · By Justin Bengry

The recent bloodbath in humanities programs has left me reeling.

Most recently there was The Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at University College London. According to the Times Higher Education, there has been a unit at UCL covering this subject since 1966. This world-renowned centre currently operates with 29 staff, including 12 academics, and 54 students, including 25 PhDs. This is a significant scholarly presence that has long led international scholarship in the history of medicine. No more. It will be phased out over the next two years.

Then there is the case of Middlesex University. Having already closed its History department in 2006, Philosophy is now on the chopping block. Opposition to the closure has gained support from scholars and public intellectuals around the world including Judith Butler, Noam Chomsky, and Slavoj Žižek. But it’s clear from stories like this that humanities programs are considered expendable, suitable victims of cost-cutting measures.

Closer to home, Canada recently invested $200 million in the Canada Excellence Research Chairs initiative. It attracted 19 world-renowned scholars to Canada, but included no scholars in the Arts and Social Sciences. Not a single, solitary one. (It also included no women!)

The connection between these stories, and others we could collect, is a denigration of the humanities. Funding priorities, department closures, and the suggestion that humanities scholars are a drain on limited resources illustrate this over and over again. There are a number of reasons for this, of course, ranging from the recent economic downturn, the ongoing corporatization of the academy, but also just an ongoing, general devaluing of the humanities.

But why do we suffer this fate? Why don’t we garner wider support? Are we too isolated in the ivory tower? I think there’s something else at play. In one way, I think we’re victims of our own success.

History remains among the most widely popular disciplines among the general public. Period films are huge money-makers, and the History Channel has been a success for more than a decade. Yet historians feel constantly under siege. Of course there can be a world of difference between popular and academic history, but it’s often a fuzzy line. We’ve done an amazing job of making our discipline interesting and accessible to non-specialists.

The consequences of this are perhaps also our biggest challenges.

Non-specialists have no problem telling me the “truth” about history, the ways people interacted in the past, the priorities my research subjects held, and the motivations of past historical actors. This is based on intuition, “common sense,” and also genuine interest. But it also positions non-specialists on an equal footing with scholars, people who have devoted at least a decade to complex questions and research. Few would tell my colleagues in nuclear physics or genetic biology, who have the same level of training as I do, the “truth” about their field, the interaction of subatomic particles, or the molecular makeup of DNA strands. But they immediately, whole-heartedly, but unmaliciously tell me all about history.

They are invested in the discipline but don’t respect its practitioners.

This equal playing field in the public’s mind diminishes the need for specialists, and their funding, and their departments. I worry that this kind of casual denigration of the humanities is what “filters” up to non-specialist government, administration, and funding bodies who enact the same assumptions in funding, hiring, and administrative decisions.

Perhaps this goes some way to explaining the bloodbath. But what is the solution? How do we remain relevant and respected? How do we bridge popular and academic history without losing the unique skills and insights that specialists offer? How will we survive?

This post was originally published at History Compass Exchanges on

3 June 2010.

Leave a Reply