Head of the (middle) class?

September, 2010 · By Justin Bengry

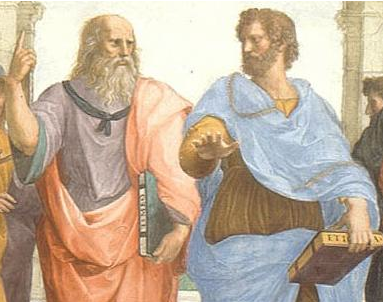

The Guardian reported today on the fear that the humanities were becoming increasingly gentrified. Reports in Britain show students from lower-income backgrounds avoiding programs like history and philosophy in favour of career-oriented studies. Why?

The study shows a fascinating, and terrifying, situation. Not only are low-income students systemically barred from higher education and advanced degrees on account of their economic resources. But we are simultaneously creating a culture around the humanities where the lowest income students are unable to take same the risk as their more affluent colleagues to pursue degrees in history and other humanities disciplines.

The study upon which the article was based spoke to enrollments and class issues in the UK, but it felt familiar even to me despite having been raised and educated to MA level in Canada and then to the PhD in the United States. The article’s discussion of working-class students’ fear of studies that might not lead in any obvious direction spoke to my own educational history.

I loved the humanities, and excelled in them throughout secondary school. But what could I do with an English degree or a History degree? With that in mind I found a compromise: I would study languages (German) and business for an international management degree. This worked for a time. I enjoyed studying German, and learning to communicate in another language opened up conceptual worlds to me I hadn’t imagined. But it was a still a compromise. The enjoyment I derived from studying German balanced against the loathing I felt for most of my business courses.

In the end I dropped out of business school to undertake studies in History. But even then, after two further years of study, I still feared I’d never find employment with the material I enjoyed, and so I left the humanities and returned to business. After many more flip flops and combined degrees I ended up completing degree requirements in all three areas: German, History, and Management. But History won as I soon went on to an MA. But some of the same concerns and struggles followed me there, as they have with other working-class colleagues who went on to graduate studies in History.

In Britain, the Guardian reports, the question of class and education is particularly significant because tuition rates are widely expected to be increased dramatically over the next few years. Increased tuition rates will, naturally, be felt strongest by those least able to pay them. And even if student funding sources are expanded, this does little to overcome what appears to be a mental obstacle preventing non-elite students from seeing the humanities as a viable option.

But what about North America where tuition rates are already on the rise? What about my former institution, the University of California, where tuition rates are growing astronomically to help offset the system-wide financial disaster? Under these kinds of circumstances, how do we maintain access for all to humanities studies?

But it’s not really about access. Grants, scholarships, and loans can be expanded for the lowest income students, after all. How do we actually convince them that the humanities are in fact a viable option, that they offer career paths, that they contribute more than ideals. And then, how do we create an academy where we can mean it, and believe it ourselves?

This post originally appeared at History Compass Exchanges on

27 September 2010.

Tags: Britain, funding, politics

Leave a Reply